Marguerite Schinkel shares early findings from a prison survey disseminated across Scotland, exploring the difficulties experienced by prisoners as a result of the Covid-19 pandemic. This is a companion piece to an article written for Inside Time which will be published in November.

A recent study on the impact of lockdown conducted by the University of Glasgow included 87 survey responses from prisoners in all Scottish establishments except for HMP Addiewell and HMP Castle Huntly.

Asked ‘how has your life changed over lockdown’, many wrote about increased feelings of depression and anxiety. Respondents said these were caused by uncertain and changed routines, long hours of being locked up, few resources with which to pass the time (with libraries closed), not being able to see family and the sense of not being adequately protected from Covid-19. People complained about only being able to clean cells once a week, having to share with others, staff and prisoners not getting face masks in time or wearing them properly, problems with social distancing and a lack of care from staff. These findings built on concerns raised elsewhere.

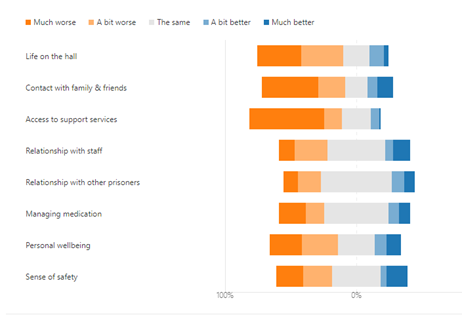

Against this backdrop of poor mental health and descriptions of rising tensions, people found it difficult to access support. One person said they had been waiting since the start of lockdown for any kind of one to one contact with mental health services, despite serious issues. Another described how they had been advised to phone the Samaritans instead of looking for support within the prison but couldn’t afford to do so. This chimes with findings provided by Samaritans themselves (see RPsych in Scotland webinars, or download slides of Samaritans July 2020 presentation here). Yet another had turned to the chaplaincy team in the face of unavailable specialised services. Physical health was also an issue, with people not having their medical needs, such as diabetes, taken into account in the food they were given, or failing to get prescribed medication in time. Some explicitly linked the above problems to completed suicides, of which there have been a number during lockdown in Scotland. The graph below shows that, overall, for most people life in prison is worse (in many cases much worse) during Covid-19, especially in relation to sources of support.

Graph: How are the following under Covid-19 compared to before?

Other respondents mentioned they had benefited from the lockdown in some ways. Some people who found the chaos of normal prison life difficult, especially being in big groups, found the lockdown regime easier, even describing it as a ‘reprieve’. Others had been able to stop taking drugs with fewer drugs entering the prison. Respondents commented positively on the introduction of virtual visits, which allowed some to see people who lived too far away to come visit in person and felt that mobile phones had made staying in touch with people outside easier. This should be read, though, against the total absence of visits at the start of the pandemic. There were also positive comments about the way that some staff had handled the situation and protocols being followed well.

These positive views ought to remind us that people are individuals and respond differently to the same situation, just as has been the case outside. Elsewhere, staff and family members have reported very negative impacts of prison restrictions, some of which might be easier to articulate for others. Support should be in place for those who struggle and Scotland’s prisons have a duty of care to provide such support immediately to those most in need, lockdown or no lockdown.

Marguerite Schinkel (@margueritesch) is a Lecturer in Sociology at the University of Glasgow and co-lead of the Criminal Justice stream of the Scotland in Lockdown study.

Description of charts on this page

This graph shows responses to the survey question ‘how are the following compared to before?’ Bars indicate the proportion of respondents that responded either ‘Much worse’, ‘A bit worse’, ‘The same’, ‘A bit better’, or ‘Much better’.

It shows that, overall, for most people life in prison is worse (in many cases much worse) during Covid-19, especially in relation to life on the hall, contact with family and friends and access to support services.